We all want to connect with our audience; stir up emotions in them. Most of us want to avoid stirring up negative emotions. Playing 16th century choral music to a pub full of bikers may not be the best career choice. But even within a particular genre, blues or metal or jazz and so on, have you tried to figure out why some players and tunes raise the hair on the back of your neck, while others send you to the exit? It's an interesting exercise that's worth going through. Is it energy, beat, harmony, virtuosity, melody, guitar sound, phrasing, rhythm?

Apart from us musicians, scientists and psychologists have been studying music too. They've discovered that something pretty amazing goes on in response to music, which seems to be something that humans have built in from birth. Very young kids recognise melodies. Natives of the far-East can listen to the first few notes of a European melody, never having heard anything like it before, and guess the next note to hum before they hear it (and vice-versa). Wow! Somehow, we get an inner sense of anticipation for what the next note should be after what we've just heard (over the last few notes), and we don't like it when anticipations prove incorrect too many times. At the same time, we love it when the anticipation is occasionally thwarted, to build an even greater sense of anticipation.

So it makes a lot of sense for us guitarists to be aware this, so we can play games with listener's emotions. What we are talking about is creating a sense of key, and playing tricks with this. Ignoring some "out-there" stuff, a tune is "written in a key", or maybe sections of the tune are written in different keys. This means that, for one section:

This first note is the key note, or tonal centre (both terms are used). The combination of tonal centre and scale type define the key. A change to either the key note or to the scale type means we have a change in key. So, C major and C minor are different keys, as are C major and B major. Strictly speaking, if we use a chromatic note (any note other than the scale notes) during the section, we're playing outside of the key when that occurs. But the point is that this is done to drawing attention, fleetingly, to what (usually scale) note comes next, so the sense of key is not lost. That said, many melodies do not use any chromatic notes.

When creating and abusing this sense of key, there are three concepts we need in our toolkit.

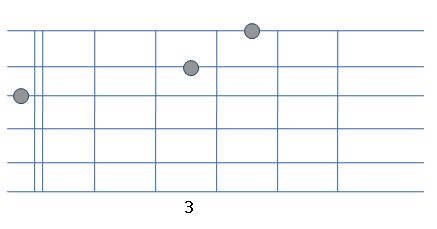

These are fairly inter-linked, and today, we'll mostly look at de-emphasis, which lets you take liberties without too many beer cans launching in your direction. To get a sense of where I'm coming from, play this chord (strings are shown horizontally, bass string at bottom of diagram. Fret number also shown at bottom. This chord includes the G open string):

<

<

Chances are that you're not too enamoured with the sound of this, and I'd lay money that you'd very rapidly want to move the G# on the top string down one fret to G, as its clashing like crazy against the open G string.

Conclusion: you better not play that G#. Well, maybe, maybe not.

You can get away with this, and sound cool, if you understand how to emphasise, and by implication, how to de-emphasise a note. So, have a short think how you could emphasise a note. Here are some ideas you may have come up with:

It should be apparent that, it you use any of the above for a chromatic note, that note is going is stick out like a piranha in a goldfish tank, and cause similar mayhem.

So, if you want to de-emphasise a note, don't do any of the above. Any of the following help: Play it no louder or quieter, or no longer than the notes before and after it. Bury it somewhere in the mid-range of the pitches (the ear is much more aware of the outer-most notes sounding at any one time). Use weak beats and off-beats. Don't jump to it. Surround it with other notes. Don't dress it up.

Let's look at this next lick that's based on G minor, but with added chromatic notes, to play over Gmin7. I've demo'ed this lick in a short example on soundcloud: it starts at 1 minute into this track. The plain backing track is there also. Feel free to download. The underlying harmony is plain … a groove from Gmin7 to F, all over C in the bass (I like the sound of the 4th in the bass)In particular, observe what beats the chromatic notes fall on. These notes are F# (7), G# (b2). The b6 (Eb) is in G natural minor, but it has a strong tendency to resolve to the 5 (D), as I've done here. Play this using 1/8th or 1/16th notes over a Gm7 chord, starting the lick on an on-beat.

<

<

Hear how the G# is no longer offensive, as it's on off-beats, and it is being immediately followed by a neighbouring G minor scale note. However, notice I've also place the F# on the beat, to emphasise it, even though it's "wrong", but it rapidly gets replaced, so the effect is fleeting.

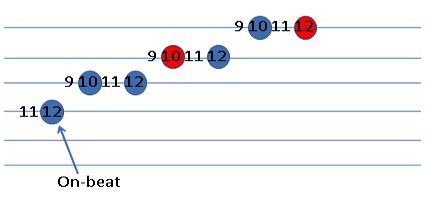

Here's another chromatic ascending lick (could be applied in the context of G blues, G mixolydian, G Lydian b7) applying exactly the same concept of using chromatic notes off the beat. It starts at 1 minute 52 seconds into this track. It's preceded by a variation of the above lick. Harmonically, this is in the key of G Mixolydian, with the solo over the following progression: Dm7/G, Em7, F maj9.

<

<

The blue notes are all chord tones (5, b7, 1, 3, 5 in ascending order). The red notes are extensions (9 and 6, in ascending order). The rest are chromatic. The lick starts on a b5 on the off-beat, and keeps the chord tones and extensions all on the on-beat.

Practise for yourself placing chromatic notes on off-beats. Most of the time, you want to resolve the chromatic note to the nearest scale note.

I hope this will give you some ideas how to play mostly in a key, while occasionally stepping outside.

In the next article, I'll talk about the importance of chord tones, and how to avoid serious sonic mishaps.

Jerry Kramskoy, based just outside London, UK, has worked as a professional guitarist in the past, briefly signing with EMI records for a compilation album (Eazy Money on Metal For Muthas II).

He studied music and guitar at the Guitar Institute in the UK, working with instructors such as Shaun Baxter, among others. Jerry's passion is to try and bring understanding of harmony and melody in a simple manner to all.