In this lesson we are going to take a look at an extremely efficient way to play arpeggios. I named the technique "Economic Sweep Picking" because it involves using more than one finger per string. For those of you not familiar with the general idea behind sweep picking, I'll review the basics.

An ODD number of notes on a string preserves the direction (ascending/descending) that you started the lick with. For example, if you started a lick with a downstroke then played 3 (an odd number) notes on single string, the next note on the next string would be a downstroke. You're probably thinking, "So what? You preserved the picking direction, big deal!" But this is very important; you have two downstrokes in a row. Now instead of playing these two, down-stroked notes with two distinct downstrokes; try playing them with one big downstroke. Simply let the pick fall to the next note. Now, don't get confused, just because you played the two notes with the same downstroke doesn't mean that the notes should overlap. The notes should sound distinct. This can be achieved by carefully muting with palm of the right hand and the fingers of the left hand.

In short, you saved one pick stroke. You're again probably thinking, "So what?" But these pick strokes that you saved add up over the course of a run. If you don't have to pick as much then it stands to reason you'll be able to play faster and make fewer mistakes than if you were to alternate pick the exact same line.

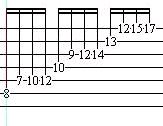

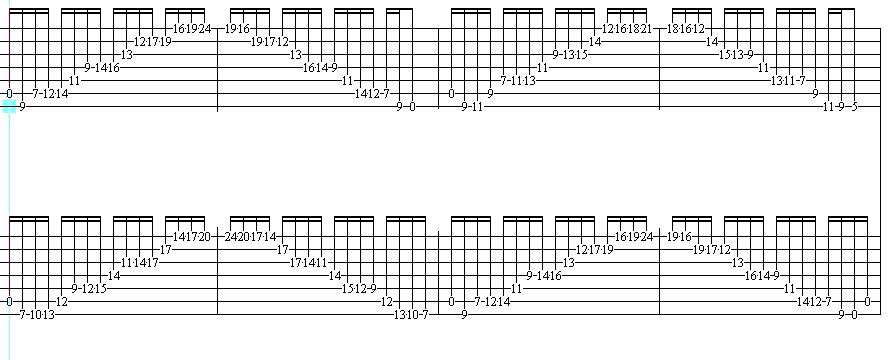

Now that was all review. Let's apply the idea to playing arpeggios or broken chords. You could play one note per string which is effective but is difficult to execute properly. There is also another even bigger drawback to this method: the patterns are difficult to memorize. Another problem is that the patterns terminate usually after only two full octaves. This last problem destroys the opportunity to play an piano-type runs. I have solved all of these problems with the technique called "Economic Sweep Picking." The crux of the technique is to play one note per string then three notes per string then one then three -- all the way through the rest of the strings. We'll start with a Cmaj6 shape at the seventh position.

The picking for this first lick goes down, down, up, and down. The first two notes should be swept. Now we need to add more notes to this arpeggio but which notes? Since there are only four notes per octave in a Cmaj6 (1 3 5 6) arpeggio and we have already played four notes, we need to move onto the next octave. This next octave is at the tenth fret, 4th string. So we shift two frets over to ninth position and then shift two string up and play the exact same shape.

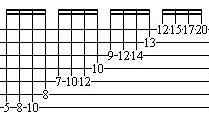

The picking for this arpeggio goes down, down, up, down, down, down, up, and down. Notice the three downstrokes in a row. These notes should be swept with one big downstroke. For those who have seven string guitars try adding on the three notes from the Cmaj6 arpeggio that go on the low-B string. These notes are E-G-A. By starting on the E, this gives the Cmaj6 an E minor pentatonic sound (no flat 7).

Now, let's move the shape around diatonically.

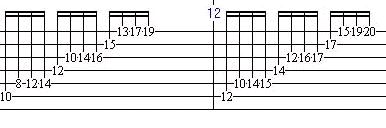

Now, lets try some wider intervals but with the exact same 1-3,1-3, etc. sweeping formula. This is an Emin7(add 13)(no 5) arpeggio. or if you started on C (8th fret, sixth string); this would be a Cadd9 arpeggio.

The big problem with the above lick is not the picking, but the fast shifting needed to get from third position to tenth position while continuing the flow of sixteenth notes. It would now be advisable to check the above lick with the "Odd no. of notes per string" rule to see if it is sweepable. The number of notes per string starting with the sixth string (low E) is 5, 3, 1, 3, 1, and 7. Those all look odd to me so this lick is sweepable.

But there is a problem: we don't want an odd number of notes when we need to turn around and start descending. To this I say, just tough it out and pick alternately on the high-E string. But make sure the first note on the B-string, coming down, is picked with an upstroke; this will make the rest of the sweep picking come out right.

This next lick demonstrates the advantage of having a seven-string. If you don't have a seven-string guitar then just play on what strings you do have. It will sound pretty much the same because the low notes are difficult to hear anyway. Notice how you don't have to take that huge position shift in the beginning that we had to take in the previous lick. To keep things interesting, let's try a different four-note arpeggio. How about an Emaj(add#11), (1 3 #4 5). Pick the first note (open E) with whatever stroke you want but make sure you pick the G# (9th fret, low B) with a down-stroke.

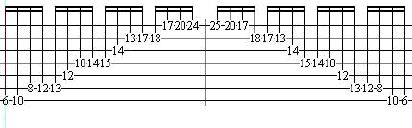

This next lick is an Fmaj7 arpeggio, but this lick is a little different in that the sweeping pattern is 3 notes per string, then 1 notes per string, then 3 notes per string, then 1 etc. -- if you don't count the seventh string. Start with an upstroke on the first note (F) then the picking goes like this: down, down, up, down, down, down, up, down, down, down, up, down. Notice how the shape changes when you reach the second and third strings; this is of course due to the fact that we tune these strings only a third apart instead of a fourth.

Finally, here is a lick taken from a piece by Franz Liszt called "Ab Irato: Grande Etude de Perfectionnement" This sums up the all of the different sweep picking ideas discussed earlier. By the way, be sure and tap the notes on the 24th and 22nd frets, but only if you run out of fingers to use on your left hand.

Marshall C. Harrison studied guitar under Brett Garsed at the Musician's Institute in Hollywood, California. He is currently living in Los Angeles where he teaches, transcribes, and records.

Marshall is a member of the "death jazz" band, K.R.A.M, which is finishing up a demo. He is also a member of the band Black Sheep.

Marshall has also transcribed in full six Chopin etudes originally written for solo piano as well as many more classical piano pieces. Email him for ordering information.